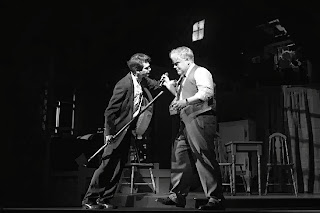

-Willy Loman, Death of a Salesman

From Jay Gatsby to Lester Burnham, the 20th century is preoccupied by the tragedy of the middle class man. Although there is an abundance of historical precedent, nowhere are these crises more palpable and poignant than this modern age where there is a chicken in every pot and everyone seeks to live the American Dream. So when I picked up Babbitt, only recognizing the name to be synonymous with conformity, (more specifically, the Oxford English Dictionary defines the term Babbitt as “A person likened to the character George Babbitt, esp. a materialistic, complacent businessman who conforms unthinkingly to the views and standards of his social set.”) I had a suspicion that Lewis’ satirical lens was an Andersonian technique of masking the underlying tragedy in order to make it more accessible. To be clear, these reflections only consider information provided through chapter VI and I do not know where this novel will lead, any suggestions to that end will be mere conjecture. However, I cannot help but see the parallel between George F. Babbitt and the salesman of the century, Willy Loman. I would like to explore these parallels and see whether Babbitt truly is a prototype of Miller’s antihero and furthermore discuss why exactly these tragic figures continuously persist throughout the century and why do we (or should we) as an audience care about these personal and professional failures?

The novel introduces Babbitt as waking from a recurrent dream in which

he is regarded as a “gallant youth” by a “fairy child” (4) Unwilling as he is

to depart from this dream, Babbitt “fumble{s} for sleep as for a drug.” (3)

This recalcitrance provides a definitive first impression of the titular

character – a man who prefers a “gay and valiant” fantasy world over the

reality of being a forty six year old made who “made nothing in particular.”(3)

This desire to escape the reality and responsibilities of adulthood is the

first clear correlation to Loman, who spends his days conversing with his

imaginary pal Ben, discussing treks up the river to discover buried fortune. In

both cases, this regressive defense mechanism suggests, at the very least, an

immaturity that neither of these characters overcame in their adult lives and,

as they are set in their middle aged ways, most likely are incapable of

overcoming. It also sets the tone for all subsequent actions in their

respective waking lives; with Loman the lines between fantasy and reality are

indelibly skewed as Ben will show up at any point to strike up a conversation.

Although Babbitt does not exhibit this extreme level of escapism (it may be

worth noting that he is roughly twenty years younger than Loman) the lines are

also shown to be blurred in his world, slipping into a reverie as he gazes upon

the visage of Ms McGoun “half identif{ying} her with the fairy girl of his

dreams” (32) It seems as if their adult world is something that has been thrust

upon them and the only relief are the imaginary scenes played out in their

mind.

Both Loman and Babbitt are family men, seemingly a requirement of their

sales profession more than anything else . I would argue that they have both

chosen spouses who facilitate the meticulously constructed artifices of their

lives. We see this in Linda Loman’s infamous concluding words to Willy’s

gravestone that she has just made the final payment on their house which meant

they were finally free, securing her lack of awareness and inability to see

freedom as anything beyond a type of material security. So too with Myra

Babbitt, she seems serenely unconcerned about her husband’s dyspeptic temper,

apologizing for the “alcoholic headache” (8) that had been caused by his own

excesses the previous night. She is more preoccupied with the appropriate

attire for dinner with the Gouches and other material aspirations found in the

society pages of the Advocate-Times. Moreover, as the history of their

courtship is discovered, we find that their marriage was more of a practical

arrangement than anything else as “of love there was no talk between them” (74)

and that Babbitt had considered her a “dependable companion” (75) This could

inevitably lead to feelings of sympathy for Myra, which is often granted to

Linda, as a victim of her husband’s narcissism and self-delusion. However, as

the novel continues, I will guard against these predictable reactions as I

recognize the wives’ failure to hold their partners accountable to their deluded reality and

to their actions is inexcusable and, in Loman’s case, fatal.

Another parallel forming between the two characters is with their

relationships to their sons. The emotional core of Salesman is in the dynamic between Willy and Biff. Not only from

seeing Willy’s fantastical encouragement of Biff and the subsequent catastrophe

such misguided love causes in the son’s life, but also Biff’s prise de

conscience, that although he is seeing who he is for the first time in his

life, his father will most likely never have such a moment. Although it is too

early to tell whether such an emotional climax is in store for young Ted

Babbitt, his ferocious interest in the homespun education courses (with the

irony, of course, that he is neglecting his actual homework) seems bound for

defeat, especially when Babbitt himself is “impressed, and {has} a delightful

parental feeling that they two, the men of the family, understood each other.”

(70) Their relationship, which bounces from antagonism to camaraderie in mere

moments, is certain to suffer from Babbitt’s conformist attitude, as Ted’s

exasperation is already evident in his attempts to force his parents to imagine

the hypothetical, “Can’t you suppose something? Can’t you imagine things?” (68)

Thus far, Ted is the only character to substantially challenge Babbitt’s

attitudes in any way and whether this will amount to anything is uncertain.

(One note to this, I’d like to point out that this scene with Ted and his parents

struck me as a momentous occasion and needed to be mentioned, despite the fact

that it does not support the argument of Babbitt as a prototype of Loman –

where the former has an incapacity to imagine, to recognize anything outside

his immediate, material existence, the latter is consistently in an imaginary

world and unable to come to grips with his present situation.)

Despite this side note, I find overwhelming indication that Babbitt

will continue to follow in Loman’s footsteps (I recognize that Loman would, in

fact, be following in Babbitt’s footsteps but chronologically in my life Willy

Loman’s narrative has concluded and George Babbitt’s journey has just begun)

and I anticipate tragedy to befall our conforming curmudgeon, whether or not it

is suicide I cannot say, but I would not be surprised. This leads me back to my

original question of why it is I would be sitting here pondering the fate of a

character I have described as a personal and professional failure? Why is it

that, no matter how many times I have seen or read the play, I always hold out

hope for Willy Loman to arrive at some kind of authentic personal, emotional or

spiritual understanding of himself as a literal “low man”? Perhaps it is the

fear of self deception (and lack of any possible self actualization) which

pervaded the post world war era which has traversed into this anxious age of

the 21st century. Seeing these psychological constructs embodied by

a literary character is both unnerving and relieving. For although I will

continue to root for an authentic awakening for Babbitt, I will join the ranks

of Linda Loman in being unable to cry at their demise.

No comments:

Post a Comment